This is the third of a three-part story. This article is based on personal research, Harvard University Archives, a 2009 interview with Robert Streich Sr., and the written reminiscences of Rudolph Jordan Jr. provided by his great-grandniece Helene Belz via the District Archives at Mont La Salle, Napa.

After Rudolph Jordan Jr. left Lotus Farm after ten years at age 32, he returned to San Francisco and began selling home insurance. He also he began making wine with a former Napa Redwoods neighbor Ernest Streich at Castle Rock Vineyards. The two were five years apart in age. Both had come from Germany at 12; both had taken on management of the family vineyard at 21 or 22. “[Jordan] was a great friend of my dad’s even though they were very different,” Ernest’s son Robert Streich Sr. said in an interview in 2009. “My dad was an immigrant from Germany who lived by his hands, a rough-n-ready guy with a grammar school education, and Mr. Jordan was from a wealthy family and was educated in Germany. But they were the best of friends.”

Because of this friendship, Streich Sr. was given Jordan as his middle name. “Mr. Jordan told me that that was a lot better than ‘Rudolph,’” Streich joked.

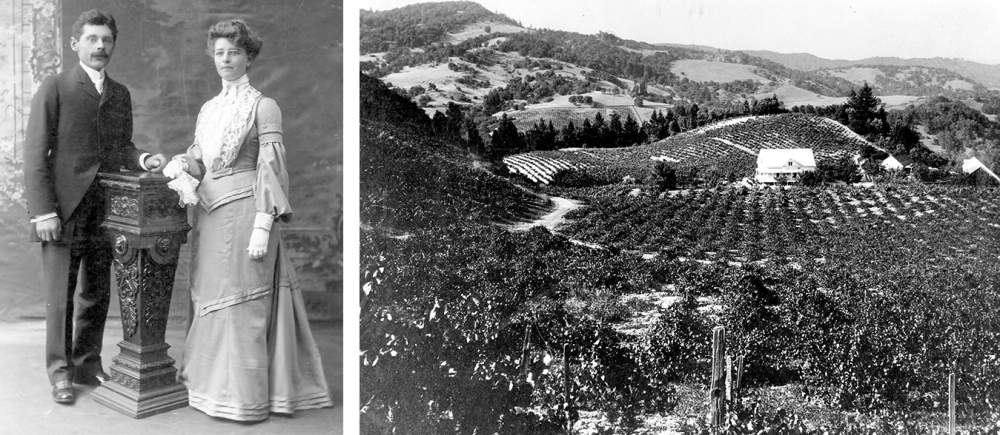

Ernest took over control of Castle Rock around 1890 when his father returned to Germany. The work ethic instilled by Ernest’s father carried on into his adulthood. Streich Sr. said his father would “get up early…work as long as he could [at Castle Rock] and then run from his place up to the canyon to [now Maycamas Vineyards] and go to work up there.” Twelve years after Ernest took over, he married Lillie Kunzel from over the ridge on Partrick Road, whose family property he passed each time he went to Napa. They had two children, Emily in 1904 and Robert (later Sr.) in 1906.

Because the Jordan family lived west of Van Ness Avenue in San Francisco, they did not lose their house in the earthquake and fire of 1906, but did apparently lose other property. With the insurance market at a standstill, Jordan Jr. told his former Harvard classmates that year in a class report that “the making of dry wines is [now] practically my vocation and I hope to return to it in the near future.”

By then he had been making wine with Streich for ten years and they had decided to try something new. Their goal was to make the best wine they could, and they had seen a recent article by Frederic Bioletti about using cold fermentation in winemaking and decided to give it a shot.

They built an elementary wine cooler in the floor of Castle Rock Winery’s cellar, a shallow pool about 4 by 8 feet and six inches deep with a copper pipe snaking back and forth lengthwise. The pool was kept full of fresh cold spring water while too-warm fermenting wine was pumped through the pipes under the water. By monitoring the temperature of the wine as it entered and exited the cooler, Jordan and Streich could see how much the fermentation was being controlled. They either added colder water or slowed or sped the flow of the wine through the pipes to control the exiting temperature. In Bioletti’s, Jordan’s and Streich’s views, cold fermentation led to wines that aged longer and tasted smoother.

Following these methods and keeping meticulous notes over five years at Castle Rock, Jordan wrote a “manual for progressive winemakers in California” that was published in 1911 called “Quality in Dry Wines through Adequate Fermentations.” Because of the book, Jordan and Streich are known as two of the first American winemakers to advocate for cold fermentation, garnering them a mention in several wine encyclopedias. (On top of this wine work, Jordan Jr. had also published a book in 1910 on the gait of American trotter and pacer horses, and how to train them, that ran to 300 pages.)

In 1913, Jordan Jr.’s wine career took another jump when he purchased the A. Repsold Wine Co., which was based in San Francisco and had offices and storage on Brown Street in Napa. He made Streich a minority owner, much of that paid for with Castle Rock wine. He moved the Napa part of the business into the Borreo Building near the river on Third Street. The wine was pressed and aged at Castle Rock and then and hauled downtown for bottling and shipping.

Before one such trip, according to Streich Sr., his father had greased the axles on the wagon, but apparently not tightened a wheel completely. Ernest made it fine twelve miles, all the way to Third Street in downtown, when the wheel got caught in one of the tracks for electric trains. The wheel buckled and the wagon shook. A barrel fell off and broke.

“Wine was leaking onto the street,” Streich Sr. said. “People came running and were dipping their fingers in it.” Soon others brought cups. Fortunately, Ernest was near enough to the Borreo Building that a worker arrived to help plug the leak and load the barrel back on for the rest of the trip.

That year Jordan Jr. married Hilde Smyth of Napa and they lived in San Francisco. A. Repsold wines made using cold fermentation won two honorable mentions and eleven gold medals at the 1915 Panama Pacific International Exposition in San Francisco, and Jordan and Streich made wine until 1920, when Prohibition took effect.

“My dad said the only difference they ever had in their friendship was over the Repsold Co. and Prohibition,” said Streich Sr. “Mr. Jordan said that the government would help them out, and he was going to hang onto his wine. And my dad’s idea was, ‘Well, if you get a chance, let’s get out of it.’” Ernest Streich got his own chance in 1921 when Henry Gier, nephew of neighbor Theodore Gier, wanted to buy much of Streich’s property, including the house and winery. As part of the sale, Streich required that Gier also buy all the wine he had in bonded storage and all his interest in the A. Repsold Co.

Ernest was 53, but ready to retire. His son said, “He had worked hard all his life…and was ‘well drilled out’ physically.” Ernest needed a rest and now he had his retirement money. “He always set his sights on making $100,000 and retiring,” said Streich Sr. “He told me ‘I made twice as much and quit [early].’”

In contrast, Jordan Jr. held onto his bonded wine. In 1926, in the middle of Prohibition and with his dreams of making quality wine in ruins, he published a third book called “At The Cross-Roads—A Plea for The Ethics of Democracy.” He told a family member he had been driven to write the book by the “coercive laws and destructive effect on the wine industry” of Prohibition. “It seemed to me monstrous to have a dictatorial government nullify property and one’s vocation without just compensation.” After Prohibition finally ended in 1933, he could not find any buyers for the stored wine. “No one wanted old wines,” said Streich Sr. “By the time he died, he still had wine left, and his wife Hilde just gave it up.”

Ernest and his daughter Emily had left the Redwoods for downtown Napa, then two years later moved with Robert to Berkley where he attended U.C. Berkeley in engineering. When Robert graduated, father and daughter moved back to the Napa Redwoods to a piece of the original property the family still owns today. Ernest traveled back to Germany eight times, often visiting Baden Baden to rest and regain his health. He passed away in the Redwoods in 1952 at 83.

This article also appeared in the January 23, 2017 edition of the Napa Valley Register.

“…The Borreo Building (which still stands in downtown Napa…”-= What is the location of the building?

LikeLike

Jim — The address is 948 3rd St, Napa, CA 94559–it’s right next to the new Third Street Bridge on the east side, stuck now alone between the river and Soscol Ave. It sits lower than grade now. Thanks for the question, Robin

LikeLike